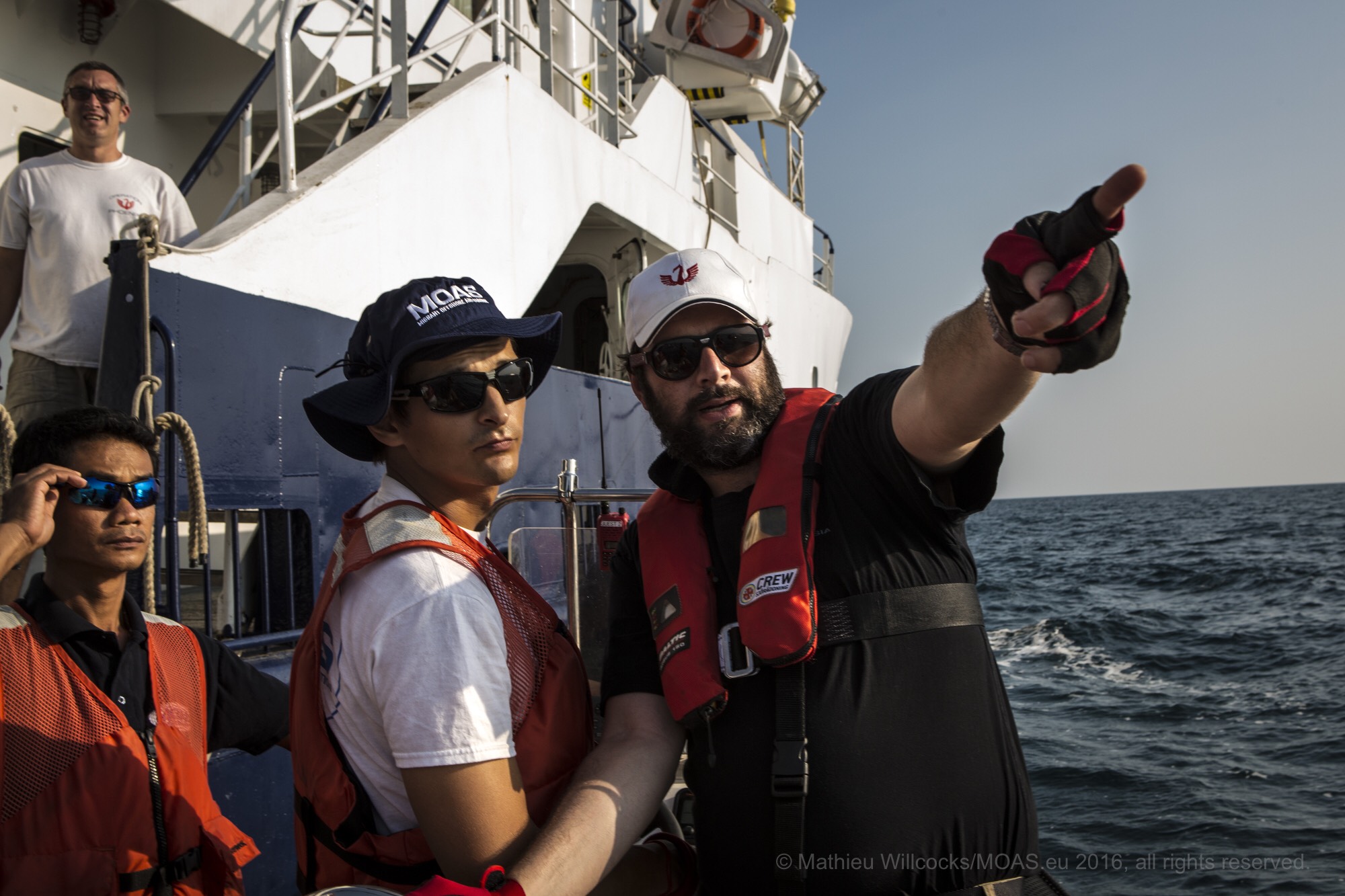

SEARCH AND RESCUE OPERATIONS IN SE ASIA | A MOAS PERSPECTIVE

A source of sustenance and a vital sea line of communication, the sea surrounding the countries of Bangladesh, Myanmar, Thailand, Malaysia and Indonesia is a hive of activity. Hundreds of vessels navigate these waters for a variety of reasons including the flight of the Rohingya from years of persecution and inhumane living conditions. Many of the vessels carrying the Rohingya are barely seaworthy.

Whilst most states provide Search and Rescue (SAR) capabilities in each state’s respective SAR region, the political and legal tangles of providing these services to fleeing migrants remain challenging. These challenges are common to most migratory routes across the Mediterranean, Asian, Caribbean, and African regions.

MOAS has been involved with mitigating loss of life at sea and reducing human suffering since 2014. Its work has mostly focused on search and rescue activities at sea, having deployed to the Central Mediterranean, the Aegean Sea and Southeast Asia with huge success. MOAS has also contributed to repatriation programmes via air transport and recently has moved in the field of land-based emergency medical support in Bangladesh. Through experience and extensive research, MOAS understands the current migration phenomenon, and can offer insight into Search and Rescue operations at sea in Southeast Asia.

Legal Position

The age-old seafarers’ tradition that assistance is provided to persons in distress at sea holds true in this region. But it’s complicated. To understand the implications, one has to unpack number of issues. What constitutes distress? When does assistance commence and end?

The duty to render assistance is enshrined in international instruments such as the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), Article 98(1) of which states that:

Every State shall require the master of a ship flying its flag [i.e.applicable to both State and private vessels], insofar as he can do so without serious danger to the ship, the crew or the passengers:

(a) to ren der assistance to any person found at sea in danger ofbeing lost;

(b) to proceed with all possible speed to the rescue of persons indistress, if informed of their need of assistance, in so far as

such action may reasonably be expected of him;

Translation:

Vessels at sea have an obligation to provide timely assistance to those in distress UNCLOS Article 98(2) poses direct responsibility on coastal States by stating that:

Every coastal State shall promote the establishment, operation and maintenance of an adequate and effective search and rescue service regarding safety on and over the sea and, where circumstances so require, by way of mutual regional arrangements cooperate with neighbouring States for this purpose.

Translation:

Coastal states need to have appropriate SAR services that can coordinate and cooperate with other SAR outfits. These two main obligations determined by UNCLOS are reinforced in the provisions of the Safety of Life Convention (SOLAS) and the International Convention on Maritime Search and Rescue.

The 1998 amendments to the SAR Convention defines a rescue as ‘an operation to retrieve persons in distress, provide for their initial medical or other needs, and deliver them to a place of safety.’

MOAS argues that for the delivery to be complete there needs to be a process of disembarkation to a place of safety. The (non-binding) guidelines issued by IMO’s Maritime Safety Committee provide a workable definition for a place of safety:

A location where rescue operations are considered to terminate… a place where the survivors’ safety of life is no longer threatened and where their basic human needs (such as food, shelter and medical needs) can be met. Further, it is a place from which transportation arrangements can be made for the survivors’ next or final destination.

The guidelines also go on to determine that a rescuing vessel is to be ‘relieved of its responsibility as soon as alternative arrangements can be made.’ The implication here is that whilst a vessel may be considered as a temporary safe place, there is also a requirement to transfer rescued persons to land to release the vessel and allow it to continue on its way.

Distress – What is it?

Paragraph 1.3.13 of the SAR Convention defines distress as ‘a situation wherein there is a reasonable certainty that a person, a vessel or other craft is threatened by grave and imminent danger and requires immediate assistance.’ The definition is further reinforced through positions taken during decided legal cases where vessels need not be sinking or aground for the vessel to be in distress.

MOAS has come across many embarkations that were in a poor seagoing state. Vessels were often overcrowded; with no navigation lights and equipment; and with insufficient fuel to complete the intended journey. Conditions for passengers didn’t fare any better, with migrants packed in every conceivable space and suffering from malnutrition, dehydration, and other medical complications. Given the circumstances, these vessels, although at times under power, were determined to be in distress. MOAS’ classification was usually confirmed by the Italian Maritime Rescue Coordination Centre in Rome.

Whilst most would agree that the responsibility to provide assistance is unequivocally clear, the disembarkation part of the solution remains open to interpretation and fraught with challenges, with political and operational implications.

Current norms and regulations are intended for the rescue of people in distress who are taken for treatment and once better, offered the opportunity to go back to their respective homes.

But many migrants can’t go home. The migration phenomenon takes into account a number of other factors such as humanitarian issues, the right to being accorded the status of a refugee, and immigration amongst others. It is immediately evident that some of the current SAR norms, when applied to mass migration, are unfit for purpose.

States may look at these matters from a ‘national interest’ perspective, citing applicable legal instruments to argue respective positioning on obligations in terms of SAR and disembarkation to a place of safety. The prime consideration for states is whether actions are perceived to ‘encourage’ flows to their mainland, hence becoming a pull-factor for potential migrants.

Over the years MOAS has taken into account the legal instruments determining Search and Rescue and applied them to the notion that ‘nobody deserves to die at sea.’ The sad reality is that statistics can never really tell us how many people perish, as most who perish are never accounted for. Given the clandestine nature of departures, one can never be sure how many persons are on the move at any given time, making a statistical approach to understanding the magnitude of the problem difficult. What is certain is that people being persecuted or living in extremely difficult circumstances will do anything to get away to a better life. It is MOAS’ qualified opinion that it is desperation that pushes people to extreme measures.

It has always been the MOAS way to engage with regional stakeholders and key players and provide professionally-capable assets to support state and other non-state actors to mitigate loss of life at sea.

Southeast Asia

Parallels can be drawn between the Mediterranean and Southeast Asian context. The principles at play remain the same, with added difficulties emanating from the non-ratification of treaties such as the 1951 Refugee Convention by certain states.

Non-signers do not recognise the status of ‘refugee’ and therefore asylum seekers are not distinguished from other immigrants, legal or illegal. However, there is still an obligation under customary international law and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights to provide temporary asylum to refugees. The current state of play sees some countries detaining migrants indefinitely, with no recourse to legal aid or the ability to apply for asylum.

Whilst the launching of a MOAS SAR mission in Southeast Asia is a relatively straightforward matter, it is the cooperation or lack of it by coastal states that becomes an issue that impacts on the viability of such a mission. To date MOAS continues its engagement progress with regional stakeholders to try and determine a way forward that will mitigate loss of life at sea. The way forward may not even be SAR operations at sea, but alternative safe migration options that look at burden – sharing, addressing issues in countries of origin, transit and destination.

What is certain is that whilst states struggle with the migration phenomenon, migrants will take to the sea, in very challenging circumstances, resulting in a huge loss of life. No one deserves to die at sea!